He had sold it. He had sold the machine that saved his back, the machine that gave him freedom. He had added the proceeds to my mother’s meager savings jar. He had literally sold his legs to give me wings.

He walked home that evening, a six-mile trek in the heat. When he arrived, he was covered in dust, his boots worn down. He didn’t complain. He simply handed me a cardboard box for my move to the city.

With worn clothes and roughened hands, he packed the box himself. Inside was everything I needed for my first month: sacks of rice, dried fish, roasted peanuts, and a second-hand alarm clock. He gripped my shoulder, his fingers digging in slightly, transferring his strength to me.

“Work hard, son. Make every lesson count. Don’t worry about us. We will manage.”

Later, on the bus ride to the city, watching the rice fields blur into concrete highways, feeling the crushing weight of homesickness and fear, I opened the lunchbox he had packed for the journey.

Tucked between the fragrant banana leaves and the rice was a folded piece of paper, the handwriting jagged and uncertain, as if the pen was too light for his heavy hand:

“I may not know your books, but I know you. Whatever you choose to learn, I will support you. Make us proud.”

The University was a battlefield of a different kind. I wasn’t fighting bullies with fists; I was fighting Imposter Syndrome with footnotes.

The other students drove sports cars and spent weekends at beach resorts. I worked three part-time jobs—tutoring, washing dishes, library shelving—just to eat.

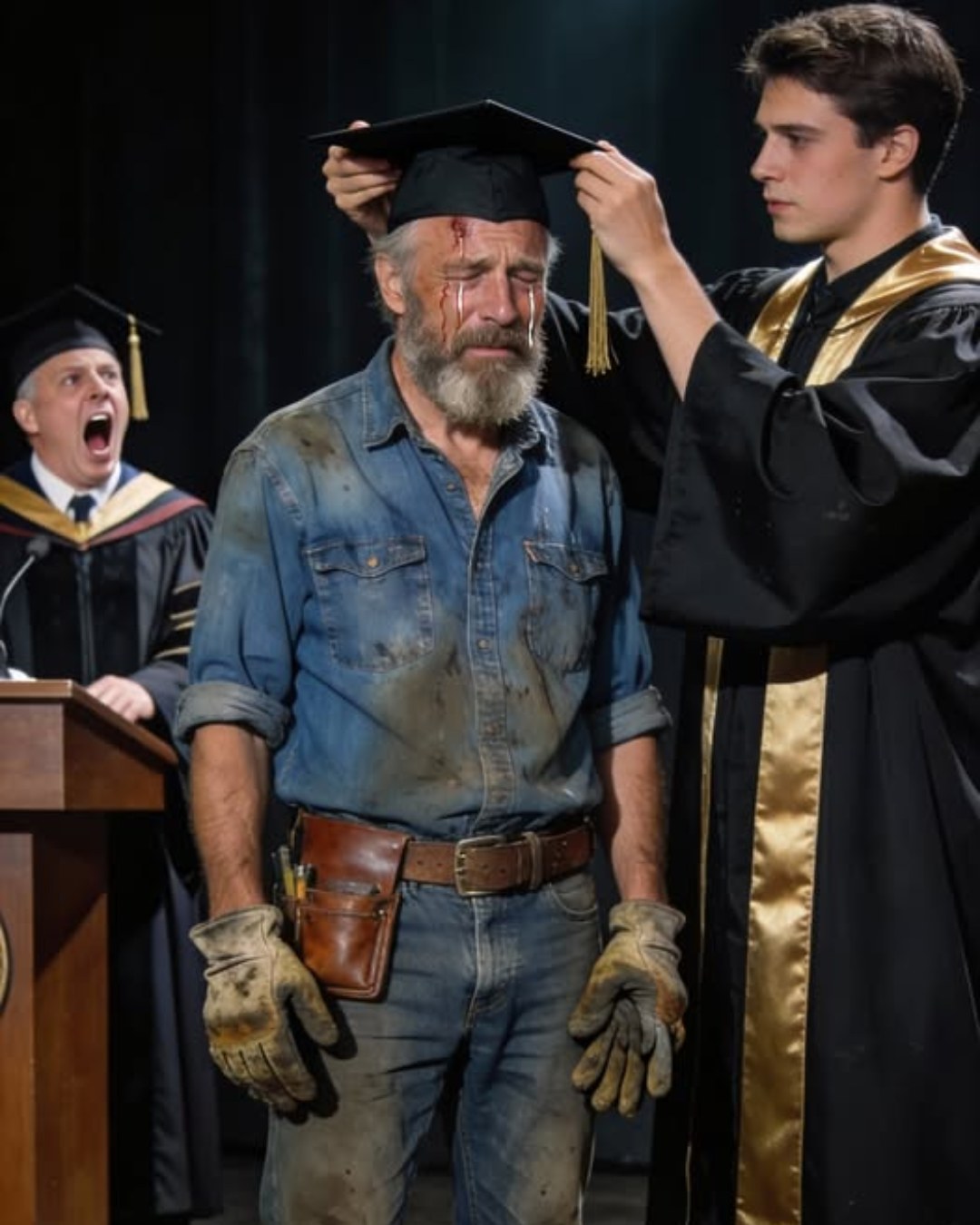

All through my bachelor’s degree and into the brutal, soul-crushing grind of graduate school, Hector never changed. While I debated philosophy, structural engineering, and advanced economics in air-conditioned lecture halls, he kept working.

He climbed scaffolds that swayed precariously in the typhoon winds. He lifted bricks under the baking sun until his skin turned the color of deep mahogany.

His back curved a little more each year, a slow-motion collapse of his own physical structure to build mine.