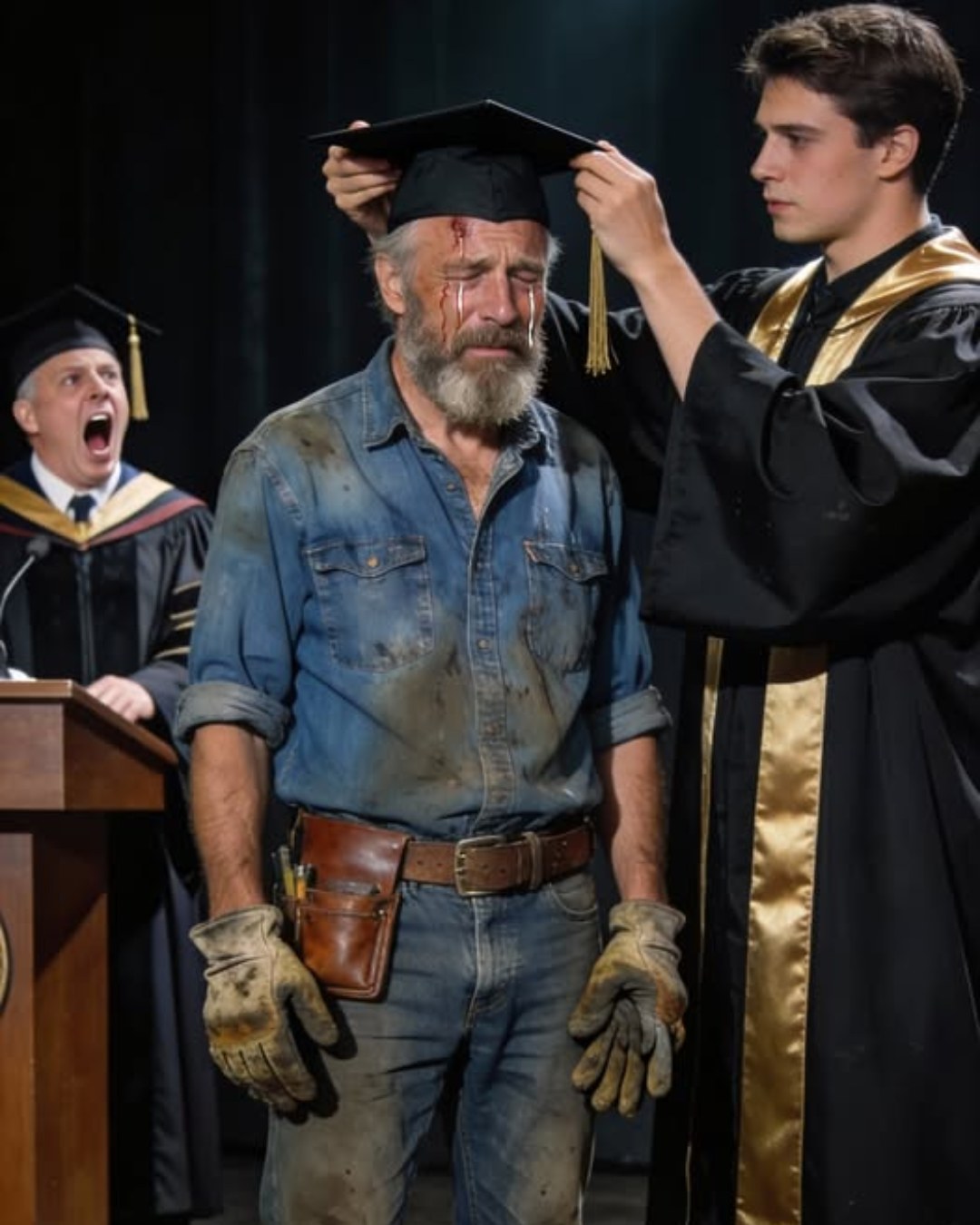

He stood there like a wall of silent granite. He crossed his massive, scarred arms over his chest and just looked at them.

The boys froze. They looked at Hector’s arms—arms that lifted cinder blocks for twelve hours a day—and then they looked at each other. Without a word being spoken, the threat evaporated. They scattered like dry leaves in a sudden wind, running back toward the main road.

Hector didn’t chase them. He watched them go, ensuring they were truly gone. Then, he turned to me. He crouched down, his knees popping audibly, until he was eye-level with me.

He took a handkerchief from his pocket—it was dirty, covered in paint spots—and gently wiped a smudge of dirt from my cheek. His thumb was rough as sandpaper, but his touch was incredibly gentle.

“Are you hurt?” he asked. His voice was soft, a gravelly baritone that contrasted sharply with his rugged appearance.

I shook my head, fighting back tears of relief.

He looked at me for a long moment, searching my eyes. “You don’t have to call me father, son,” he said, the first time he had ever addressed the elephant in the room.

“I know I am not him. But know that I will always be here when you need someone to stand in front of you.”

He stood up, dusted off his knees, and walked back to his bike.

“Hop on,” he said. “I’ll take you home.”

From that moment on, the word “Dad” came naturally. It wasn’t forced. It slipped from my lips before I even realized I had said it, born not of biology, but of gratitude.

Life with Hector was simple, but full of a profound, unspoken meaning. As I grew older, entering high school, the gap between my academic ambitions and our financial reality became a chasm. I was a good student—top of my class—but in Santiago Vale, intelligence was often suffocated by poverty.

I remember how he walked through the door every evening. The uniform changed colors depending on the job—white with plaster, grey with cement, red with clay—but the exhaustion was constant. He would slump into the wooden chair, his hands shaking slightly from muscle fatigue, but he would ask only one thing:

“How was school today?”

He couldn’t tutor me in calculus. He looked at my physics textbooks as if they were written in alien hieroglyphs. He couldn’t distinguish between Shakespeare and Cervantes. But he pushed me to study with a ferocity that bordered on obsession.

He would sit on the porch, smoking his cheap, unfiltered cigarettes, watching the smoke curl into the humid night air, repeating his mantra:

“Knowledge is something no one can take from you. It is weightless, but it is the heaviest weapon you can carry. It will open doors where money cannot. It is the only key, son.”

Our home didn’t have much. The roof leaked. The floor was bare concrete. Yet, his steady resolve gave me strength.

Then came the day the letter arrived. The acceptance letter from Metro City University. It was the most prestigious university in the region, a place for the children of politicians and tycoons.

I had gotten in on merit, but the scholarship only covered tuition. Living expenses, books, food, rent—it was a fortune we didn’t have.

My mother cried with pride when she read the letter, her hands covering her face to hide her sobbing. But then her tears turned to despair as she looked at the breakdown of costs. “How?” she whispered. “How can we send him?”

Hector didn’t say a word. He took the letter, read the numbers slowly, his lips moving silently. Then he went out to the porch and sat there for hours, staring into the darkness.

The next morning, I woke up to a strange silence. The usual coughing roar of the motorbike was missing.

I ran outside. The space where his motorbike—his prized possession, his only mode of transport to jobs thirty miles away—usually stood was empty. There was only a patch of oil on the dirt.