In their place came the memory of scorching heat, the drone of cicadas, and the overwhelming, metallic smell of wet mortar and sweat.

I wasn’t a Doctor of Philosophy in that moment. I was just a boy from Santiago Vale, looking at the man who had built me out of nothing.

My childhood was far from the idyllic scenes painted in the storybooks I later devoured. It was a life drawn in charcoal—messy, dark, and easily smudged. My mother, Elena, was a woman of fierce love but fragile circumstances.

She had the beauty of a wilting flower, holding on desperately against a harsh climate. She had left my biological father when I was barely walking.

His face had become a blur over time, a ghost haunting the edges of my memory, eventually replaced by the reality of empty rooms, unpaid bills, and unanswered questions.

Life in the small town of Santiago Vale was harsh and modest. It was a place where the rice fields stretched endlessly, shimmering like green oceans in the heat, and the streets were paved with dust that turned to a thick, clay-like mud when the monsoon rains came.

In our world, affection was measured not in words or gifts, but in survival. Love was the minutes someone returned home safely from a dangerous job; love was the extra scoop of rice placed before you on a chipped enamel plate while the server went hungry.

I was four years old when the dynamic shifted. My mother married again.

Hector Alvarez didn’t bring status. He didn’t bring wealth. He didn’t arrive in a car or with a bouquet of roses.

He walked into our lives carrying a faded red toolbox that rattled with the sound of iron, his hands calloused into something resembling tree bark, and a spine already shaped by years of carrying the world’s weight.

I resented him at first. To my childish, wounded eyes, he was an intruder. I wanted a knight; I got a laborer. I wanted a father who wore suits and drove a car; I got a man whose hands always smelled of mortar, cheap tobacco, and diesel fuel.

His heavy boots tracked red dust across my mother’s clean floors, and his conversations at dinner—when he wasn’t too exhausted to speak—revolved around job sites, concrete ratios, and the price of rebar.

I couldn’t picture his world. I didn’t want to. I remember watching him from the doorway of our small kitchen, my small arms crossed over my chest, judging him for his silence. He wasn’t the dashing hero I had fantasized about; he was just a worker, a man of dirt.

“He’s not my dad,” I would whisper to my mother when he was out of earshot.

“He is a good man,” she would reply, her eyes sad. “He is trying.”

But he didn’t try in the ways I understood. He didn’t play catch. He didn’t read me bedtime stories. He simply worked.

He would leave before the sun rose, the roar of his ancient, secondhand motorbike waking me up, and return long after the sun had set, a silhouette of exhaustion framed by the doorway.

It took years—years of silent observation—before I began to understand the language he spoke. It was a language of action.

He noticed my bicycle had a loose chain that kept slipping, bruising my ankles. One evening, without saying a word, he sat on the dirt floor of the porch, grease staining his fingers, and aligned the chain with surgical precision.

He patched up my worn-out sandals with heavy twine so I wouldn’t have to walk barefoot to school. He fixed the leaking roof in the middle of a typhoon, slipping and sliding on the wet tin while I watched from the window, terrified he would fall.

But the moment that truly shattered my resentment happened when I was eight years old. It was the day the shadows of Santiago Vale grew long and dangerous.

I was cornered behind the old, dilapidated schoolhouse by three older boys. They were the kind of boys who smelled of trouble and neglect, their eyes hard and mean.

They wanted my lunch money—a few meager coins Hector had pressed into my hand that morning before leaving for a site in the next town.

“Empty your pockets, runt,” the leader sneered, shoving me into the rough brick wall.

Fear paralyzed me. My throat closed up. I clutched the coins in my pocket, knowing that money was meant for my lunch, knowing Hector had worked an extra hour to earn it. But the boys were bigger, stronger, and hungry for violence. One of them raised a fist.

Then, I heard it.

The distinct, rhythmic rattle of a rusty chain. The sputtering cough of an engine that had seen better decades.

Hector.

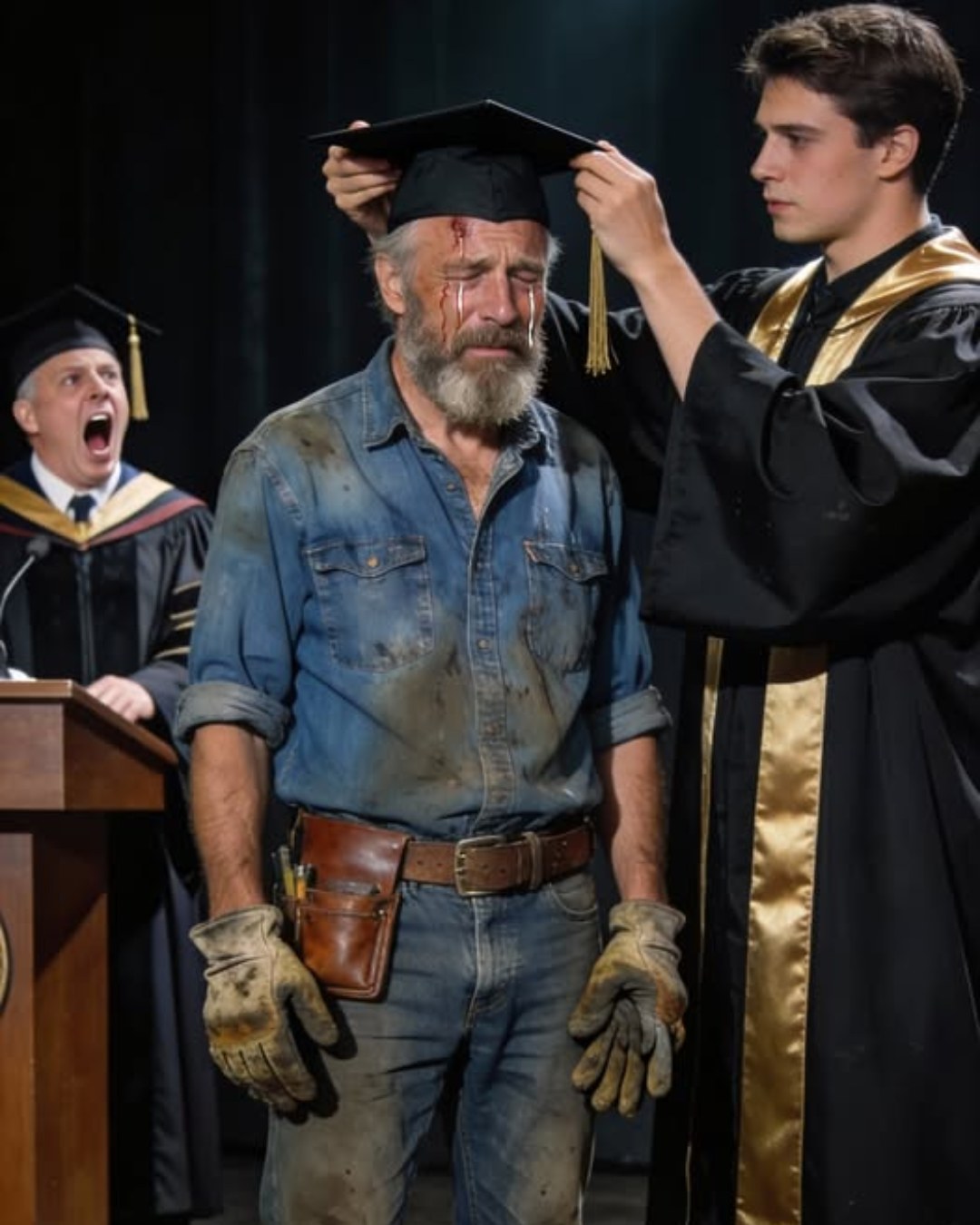

He must have been passing by on his way between sites. He skidded his bike to a halt, dust clouding around him like a dramatic fog. He didn’t shout. He didn’t scream. He didn’t raise a fist. He simply killed the engine, kicked down the stand, and stepped off the bike.

His construction boots hit the ground with a heavy, ominous thud. He walked toward us, still wearing his yellow hard hat, his work vest stained with sweat and plaster.

He didn’t run. He walked with a slow, terrifying deliberation. He stepped between me and the bullies, turning his back to me, facing them down.